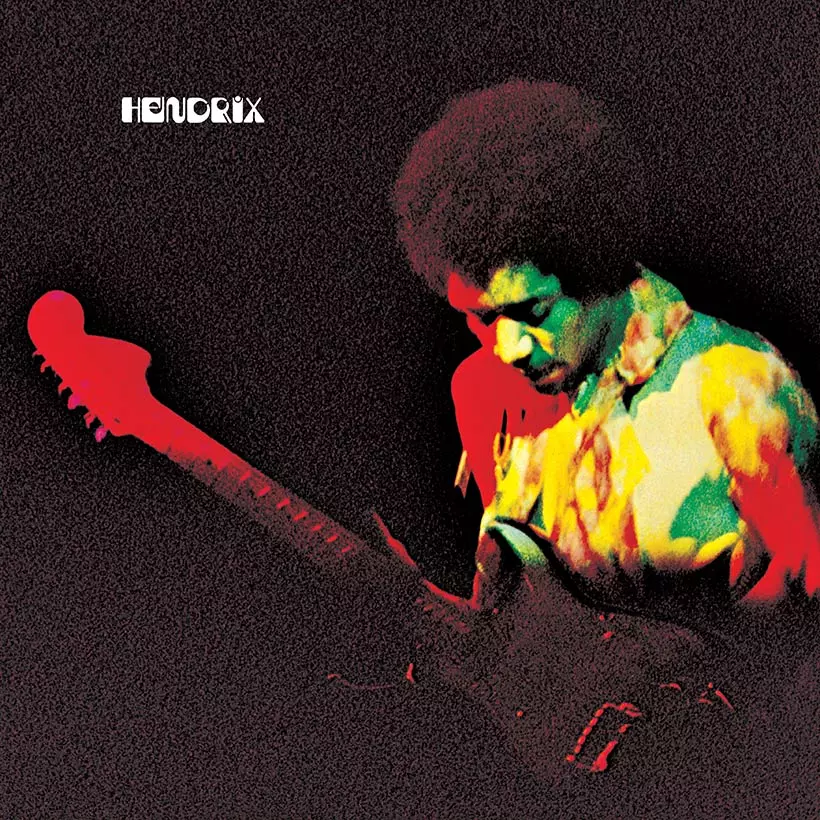

“Band of Gypsys” (1970)

On the shelf nearest to the first-floor staircase in my school library sits the most racist piece of text I’ve ever read in my life.

I stumbled upon it a couple of weeks ago.

The essay, one amongst many in an anthology, is an investigation into something called “negritude”: a sociological concept premised on the idea that the African black possesses certain physiological & psychological attributes that are essential to his nature, that uniquely determine his subjective experience of the external world, and that render him ipso facto fundamentally distinct from the European white.

I had a couple of other titles laid out next to my laptop and had planned on skimming through each one of them. But when I got to that essay I was immediately transfixed. I couldn’t believe what I was reading:

The African Negro … lives outdoors, both off the earth and with it, on intimate terms with trees and animals and all the elements, and to the rhythm of seasons and days. […] The European White … first of all distinguishes himself from the object. He keeps it at a distance, immobilizes it outside time and in some sense outside space […] Armed with precision instruments, he dissects it mercilessly so as to arrive at a factual analsis. […] He treats it as a means. And he assimilates it … destroys it by feeding on it. […] The African negro is as it were locked up in his black skin. He lives in a primordial night, and does not distinguish himself, to begin with, from the object: from the tree or pebble, man or animal […] He does not keep the object at a distance, does not analyze it. […] He turns it over and over in his supple hands, touches it, feels it. […] By their very psychological makeup, their behavior is more lived […]

[…] The reason of classical Europe is analytic through utilization, the reason of the African negro, intuitive through participation. […] This method, which consists in living the object … is a matter of participating in the object in the act of knowledge; of going beyong concepts and categories … to plunge into the primordial chaos, not shaped as yet by discursive reason. […] It is the attitude of a wide-eyed child; the attitude of the African negro. […] The world of magic is, for the African Negro, more real than the visible world. […] ‘I think, therefore I am,’ wrote Descartes … The African negro could say, ‘I feel, I dance the Other, I am.’ Unlike Descartes … he has no need to think, but to live the Other by dancing it.

Wait, it gets better. Here’s my favourite—and, to this here project, the most relevant—part:

And thus the Negro—the African negro, to return to him—reacts more faithfully to stimulation by the object: he espouses its rhythm. This carnal sense of rhythm […] When I see a team in action, at a soccer game for example, I take part in the game with my entire body. When I listen to a jazz tune or an African negro song, I have to make every effort not to break into song or dance, for I now a “civilized” person. George Hardy wrote that the most civillized negro, even in a dinner jacket, always stirred at the sound of a tom-tom. He was quite right. […] A friend of mind, an African negro poet, confessed to me that every form of beauty hit him in the root of his belly and made a sexual impression on him. Not only the music […]

—Senghor, On Negrohood: Psychology of the African Negro

Remember him? I certainly do: he’s currently sitting at the very bottom of a carton full of old textbooks somewhere in an unlit corner in my father’s house.

Anyways, I’ve spent recent weeks going through texts and footage I’d long archived trying to understand what my earlier fascination was with the subject—one into which there’s hardly never a detour whenever any question arises whose solution sits perfectly on that intersection of history/biology/mathematics. (Specifically: post-colonial/genetics/statistics.)

Fascinated as I am, though, by Senghor’s essentialist views on race—and it would be interesting to know how and whether they informed Senegalese policy—I am urged first-and-foremostly to the question of how they square up to contemporary prevalent culture.

My eternal reference: Binyavanga Wainaina.

A self-avowed Pan-Africanist—of the Ngugi-wa-Thiong’o-type and perhaps even stronger—Binyavanga espoused a political candor that, in my opinion, remains unmatched.

His work, riddled as it was with questions of time and culture, wasn’t really an attempt at a solution, but rather an invitation to stew peacefully in the conflicts; to think through the issues along with him.

For starters, while seeing the value in preserving the cultural aspects of ethnicity, he eschewed ethnic chauvinism in all its forms; at one point, in early blog correspondence from the mid-2000s, actually foreseeing the coming skirmishes:

This present wave of “uGikuyu” seems to have sucked up a whole generation of people: who believe that the future of Kenya lies ONLY under a Gikuyu umbrella. To me this seems like crazy and corrupt politics, capitalising on the post-Mau Mau and post Kenyatta entitlements and paranoias that have been past on from parent to child, often without explanation or analysis – and now what is we have is a vague formless fear of the unknown from the ‘other side’. […] I find I cannot be silent about the politiking and the text messaging xenophobia that has infected, it seems, all sensible Gikuyus. I say this because no prominent people are speaking against this: this insane kitchen cabinet of an insane presidency is using fear to keep Gikuyus on their side, and this is causing serious damage to our place, and the place of our children in a future Kenya. Not even the Moi Kalenjin junta caused so much social and tribal friction, in such a short time. […] Some friends of mine have said that we are “owed” because we “suffered” under Moi. Who did not suffer under Moi?

—Binyavanga, A Letter to My Father, B&H

Dear Wainaina, I am sorry that at the age of 35 we have to talk about this issue. But it seems you have a few things mixed up .First let me correct you. You are a kikuyu first and a Kenyan second. Long before the colonial government formed Kenya you were a kikuyu and long after the united states of Africa forms you will still be a kikuyu. […] My dear son do not be an apologetic for who you are. Do not be ashamed of your blood and your heritage. […] Son yes it is in did true that the village mad man is our mad man and when a choice has to be made between our village mad man and the other villages mad men, i think i would rather support our mad man.Until other contrustive villagers in our village or the other village come up.i am sorry to say i trust our mad man.You see my son that is the very problem we face a lark of choice.Given two bad choices then we have no other option but to choose the one we can relate to at some level. […]

[…] On the issue of the oath . you dont need to worry about that. when you were born you were automatically oathed remember i said ‘Nyumba ya Gikuyu and Mumbi igikajeta—nigeteka!’ […] trying to demonize leaders wont help sure you want a change in kenya we all want a change but what are you suggesting that we replace kibaki karume and michuki for raila,ojode and otieno kajwang. come on get serious […] you continue your propaganda ,but come december 2007 we shall settle this mess once and for all. […] i dont live in an idealistic world. i used to , when i was younger. i now live in a practical world. if you are not the ODM youthwinger that i think you are, why havent you criticized the thieves in ODM,the looters and those who made others lie low like envelopes in the past. […] i am being realistic believing we can change things from within as young people but you being the railamaniac i think you are want a revolution with a lynching of all kuyks to go with it. […] why dont you tell us of the kojwanga’s and the stolen clients money, the ntimamas and the kikuyu blood that flows from his pangas.have you developed selective memory. Has the rwanda experience taught you nothing.was it only tutsis who died or did hutu’s suffer also.Revolutions dont work in africa their results are only bloodshed […] Binyavanga why are you walking on such dangerous ground. Why has hate filled your heart? Was being born with an ordinary spoon that bad that you have to hate those born with golden spoons. […] Binyavanga the more you write the more you reveal your true nature a liberal to the core. No wonder you support raila to the core. To the core of re-distributing wealth. […] Does being born in the ruling classes’ mean you were born of the devil. Maybe a public trial and gallows in kibera once Raila wins. The whispers of the snake the whispers of the snake .Eve heard it now Kenyans hear it. the whispers of a snake hisssit’s the kikuyus, no it’s the rich no it’s their children .No! NO! It is us for listening to the snake… The whisper of the snake can you hear his hissing. Listen to your uncle, where is the hope where is the joy? The snake in us all doesn’t have to whisper when the reason in us all shouts!

—Uncle Joe, comment section

Brittle things crack and break, they crack and break. Who froze things to make them so rigid […] Why can the uncles and fathers see they have lost their sons? […] We inherited brittle men – unable to cope with the times and stewing in dissatisfaction and drink – and repeating mantras, refusing to participate in family, and leaving the dynamism to the women who filled the shoes. […] What was completely ommitted was the fact that Brawan (who is not a Luo) is an example of a young Nakuru guy, born in the wrong side of town, who has made something meaningful of himself – and is an example to many. He is more connected to what Nakuru really is than Mirugi junior. And all those jobless young Gikuyus in Nakuru were deceived by paranoia […] Over the past three years, a cadre of fat and rich wazees have been financing a “Gikuyu revival” – this looks nice and happy on the surface – but most of its substance is the spreading of hate speech against all other tribes – the idea being that “we” are somehow special and godchosen to lead Kenya – because the rest are crazy or lazy. The “barbarians” need to be kept to their “areas” – while ‘we’ move around with impunity. […] There are some people talking to young people all over the country, to be aggressive about their political demands – but many Kenyan abroad keep fanning the idea of this new uGikuyu – and ignore the fact that is will benefit no ordinary Kenyan, and may lead to blood on the streets. I urge all thinking Gikuyus to completely ignore any attempts to fan your tribal pride – this is the single biggest hurdle facing us in building a meaningful government. The purpose of this is to continue to fuck you, and your children and their children, as you have been fucked since 1952.

[…] The idea that one chooses a thief of one’s tribe over sensible person of another is insane – and scary when ordinary educated people start talking like this – the tone and intensity of the dislike and propaganda is worse than it was in 69, and threatens good order in Kenya. […] There is a lot more in Kenya. ODM and NARC are now what we deserve because we are refusing to dream better. The space is open – but we have inherited habits from the old political system where we imagine the basic options thrust at us are all that can be on offer – the space is wide open.

[…] But hate is mathematical: for when people come under the slogan of hate: such and such people are like such and such – all relationships that derive from this shall be symmetrical. It becomes easy to cut away, end friendships, and kill wives when the symmetry of hate is clear within you. […] Maybe the way our Uncle Joes flirt with this rhetoric is simply because we have never been at war. We have seen, over the past century, time and time again, whole groupings butchered based on words that sound exactly like Uncle Joe’s. […] The idea behind this, of course (Kenyan politics is very crude – it is us who try to put in pethos) – to suck you into the Soap Opera of two players – and escalate the shit, till we are all standing behind walls with machetes and voting cards saying ai even if I went to a National school, those Luos, those Luos, those Luos…and at some point the Luo ceases to become a person. Anybody questioning NARC Kenya becomes an “ODM Youth Winger” …and that is a declaration of war. What Uncle Joe said was he is at war. Rwanda is not an example, to him, of how not to do it – it is a territory of “similar examples” to justify his war-like stance. What is actually being said is: there is no room for other – and we all know, there is no conversation or debate to be had with a youth winger. You either flee or fight. And of course, we are not yet in 2007. In 2007, what would Uncle Joe be invoking to show his fears: for if the Youth Winger is the lowest, most violent of Kenyans, the rung below that is bestial, no longer human. And once people are persuaded that a whole group of such are a-comin’ they are a comin’ to getcha…… Now Uncle Joe has made it clear he is not “fleeing from the beast” so I guess he is “fighting the beast” So fight, bwana. Fight away. Meanwhile – let us all remember, all these warlords, ODM, NARC – when the accounting is done – they all own shit in each other’s backyards. They are partners and need to make this temperature so we never realise who the real enemy is. […] if The Gikuyus can be made to hate; the Luos made to hate, the Kalenjins made to hate – they are easy to manage, and rob. They will defend their mdosi to the bitter end. […] The most comical thing about all this is the children: you will see the children of warlords whose “tribes” are butchering each other, visit each other’s homes, date, marry, party together, go to the same schools and attend each other’s weddings. While you foam at the mouth for your leaders, their children are very happy having multi-tribal sex and fun and compassion even – they can afford it. And each successive government will need to do exactly the same thing to finance this lifestyle. So long as their loyal defenders continue to carry their flag.

—Binyavanga’s reply

He was incredibly critical of (and much less conflicted about) the Western gaze, making clear his skepticism towards aid programs and the bleeding-heart pathos behind the whole enterprise —

If you look at the website in Kenya of any Western embassy, they talk about partnerships for development. And then you see a lot of school children suffering and then being helped by the ambassador. But they don’t list the companies that are operating here. So its the question of ‘What’s the full picture?’

[…] I came back here in 1995 to work. My father and a group of people bought a cotton ginnery those days of privatisation. I traveled [through] seven districts in Kenya. I was shocked. I went to a government [agricultural] extension officer here in Kenya and they told me ‘No, I can’t leave my office until you pay me the per diem that PLAN [International] pays me to leave here and service the farmers. That’s a paid government official. I went to districts where the chief, the D.O., the D.C., and the community members were like ‘If you don’t invite plan to the meeting, we can’t start to talk about cotton.’ That’s neocolonialism. […] So then you start to hear [of] a country that was feeding itself 15 years ago, ‘There’s a drought in Ukambani, they’re calling the donors’. Why? It makes the job easy. The MP doesn’t have to do anything. That level of dependency is a power game. […] So when that cotton business had collapsed in those areas, it had collapsed very directly because you couldn’t give farm subsidies anymore while [the] Europeans could! That’s neocolonialism.

[…] There are arguments that you could make that are valid on the question [of whether corruption is part of the colonialist legacy]. The rise of elites; who was lifted from the ground; who partnered with the British and got huge rewards—that’s rife all over the continent. Of course, we’re now 50 years after colonialism, and we’re dealing with a place where we’re sovereign, self-determined nations that control their own fate. So to hark back to that also is looking for a kind of victimhood that’s not helpful.

[…] The Chinese hunger for things poses all kinds of threats and opportunities for us and everybody. But I’ll also say I’d rather do business with someone who says ‘I’m going to buy your thing for so much’ than the person who tells me ‘I’m donating red-cross blah blah humanitarian blah blah’ all that nonsense while they’re still messing you. Right now, in terms of economic influence, the West’s influence and its bad terms of engagement, and bad terms and contracts, remain very strong on this continent. […] The West’s relationship to Africa is not transparent at all. Everybody’s impression in the West is that ‘They’re just being good over there’, and they’re not.

—Binyavanga, Al Jazeera

— yet remained firmly in favour of Western-style liberal democracy in Africa. Gay rights, due process, civil liberties, sovereignty + self-determination, a forward-looking national ethos—the whole deal.

On the link between neocolonialism and ethnic violence, he said:

[…] Kenya and Côte d’Ivoire, Kenyatta and Houphouët-Boigny, decided to go the route of ‘Wait for these people to be ready to receive political liberation. Allow the multinationals. Allow everybody else to come in. Allow that growth to happen.’ It happened. But our political system kept people down to a point at which … [Interviewer interrupts: Are the ethnic tensions that we hear about often in Western media—is that over-exaggerated, you think?] I think it has been exacerbated by how the political system works. It’s very base, I’m sorry to say, and extremely medieval. That’s what I was trying to tell you: In 30 or 40 years, there was no thought on how to make useful political systems on the ground for people to relate to each other. And that’s why you see where Côte d’Ivoire went and where Kenya went. And that’s why Ghana didn’t go there—they had their coups and everything, but they did build a solid political identity as a country, and were then versatile and muscular. Kenya finally [learned] painfully the cost of that […]

—Binyavanga, Al Jazeera

And on the link between anti-gay rhetoric and the racial essentialism of the Victorians (and Senghor), he said:

When you look at the map of gay rights around the world, why is ours bright red and then the other ones are soft gentle blue? Because guys learned! After many died, after ma-holocausts happened. Guys were like: ‘You know what, it’s now worth it to find mkosano about what a grown up is doing in their bedroom, so just choose not to like it.’ […] So, for example, you go on Facebook and you find somebody with three degrees who went to a good school saying: ‘Africans are natural. And that’s why homosexuality is bad. Africans are just natural.’ Which means ‘Africans are close to nature.’ Which is coming from ‘these Africans are near apes’. So now you, you don’t see whose job you’re doing for free.

—Binyavanga, We Must Free Our Imaginations

At the moment, I still struggle with the implications of his radically anti-interventionist sentiments:

And then if you Google enough, there will be someone with a child just like that looking at you and telling you, ‘Click here and send a dollar.’ So you pay some guilt money. But then after a while, you’ve paid some guilt money, and next year you’ll need something more horrific to notice, because you get more and more numb the more and more horror you witness. So you have this campaign that’s going, you know. I don’t even know how much our GDP has fallen because of just the ubiquitous photographs of us looking like that. I don’t know for every dollar given in that way how many dollars of somebody wanted to invest in a business in Nairobi have gone away. […] And so the ethics of those pictures to me … are upsetting, because someone just keeps telling you the urgency of the situation. People in Darfur are dying! I’m like if you have to dehumanize people to that degree, for them to die. If it is that the Western audience is so inattentive to a possible genocide that that is what you have to do, don’t do anything. Leave us alone. [Interviewer: Really?] Yes! Let us just solve our own problem. That should not be a way that human beings deal with each other.

—Binyavanga, On Being with Krista Tippett

Binyavanga didn’t hesitate to shut any door that would lead to hindrance of his own ability to fully self-actualize and self-define as an African. But it made him, IMO, a bit too selective at times.

He appears to have had (in the early days, anyway, and he admits this himself) something of a blind spot, for instance, when it came to granting Westerners the very agency (to observe and think and surmise) he wished Africans had.

In writings he made between 2005 and 2007, he wrote scathingly about Ryszard Kapuscinski, a Polish writer whose work, by Binyavanga’s admission, is what single-handedly provoked him to write his renowned essay How To Write About Africa.

Binyavanga calls him a “fool,” claiming that “a naked social Darwinism underlies all his work”:

I am in the US, on a reading tour and just found out that Ryszard Kapuscinski will be speaking at various fora in New York City […] He often speaks about the continent to people who make serious decisions about us. And he is a fraud. A liar. And a profound and dangerous racist. I urge you all to forward this to all concerned African and writers you may know; and to email a protest to PEN International […] Another confession: the secret gagger in me wants him tied and bound, but I know this to be futile and unhelpful. Why does the instinct to gag rear its head? Because any African knows the particular flavour and danger of his kind of language. It is responsible for many deaths. It is the language that seeks to justify your incapacity, to distance your humanity from his centre.

[…] By asking why they invited him, I was not suggesting they gag him – his books are widely available in mainstream bookshops all over Europe and America. Penguin love him, and publish him. But, there are many great writers. What I ask is, Why Kapuscinski? Is PEN America’s open-mindedness so open that they would invite a known and racist and bender of well-documented fact to their most important event? Where the ‘select’ are called? How are we to read this? Am sorry. I find it hard to believe that the effect of PEN’s action will be an ‘exposure’ of his falsehoods. […] Whatever happens in New York, he will add to his CV, and get better and bigger book-deals, and have more ‘authority’ than he had before… I wish I believed in the inherent free-flow of ideas that would suggest that, as (you say) the Yoruba say: “A lie may journey for twenty years, soon Truth will break its spell, in one day”. In these days of spin and the power of one broadcast to reach a whole world, the truth is that it is those closest to the nerve centre of ‘the broadcast’ who will impose their truths on the rest of the world. […] Of course we will continue to write. But are you suggesting avoiding protesting what others write about us, simply because our writing will ‘replace’ them? That is not true. Conrad is as influential now as he was then … and Ryder Haggard is still in print…is still available in AFRICAN libraries… […] I do not see the logic behind an argument that says that one’s only response should come from one’s writing. […] So I am maybe trying to understand PEN America’s reason for inviting him: that maybe everybody’s voice should be represented? Even the unreconstructed racists? His short and snappy sentences? Or the larger truths he has brought out that make his Victorian attitude towards race somehow palatable? Is there not, somewhere, a line drawn?

—Binyavanga, B&H

Among the worst (to me) of what the Polish anthropologist-type appears to have said is that:

Let us remember that fear of revenge is deeply rooted in the African mentality, that the immemorial right of reprisal has always regulated interpersonal, private, and clan relations here.

[…] Africans believe that a mysterious energy circulates through the world.

[…] The European mind is willing to acknowledge its limitations, accept its limitations. It is a skeptical mind. The spirit of criticism does not exist in other cultures. They are proud, believing that what they have is perfect.

—Kapuscinski, The Shadow of the Sun

Away, but not too far, from the subject, I’ve also been skimming through two other titles—one by Michela Wrong and the other by Charles Murray—and, again, page-after-page I find myself wondering what Binyavanga would have thought about their writings.

Wrong’s book about the 2013 murder of a former RPF member is prefaced by some rather sobering statements:

One of Rwanda’s prime ministers, Agathe Uwilingiyimana, shocked the head of a UN peacekeeping force by telling him: “Rwandans are liars and it is a part of their culture. From childhood they are taught to not tell the truth, especially if it can hurt them. […]”

[…] “Lying is the rule, rather than the exception.” […] “Of all the liars in Africa, I believe the people of Ruanda are by far the most thorough.”

—Wrong, Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad

Murray’s book is a much more difficult read, and not because it is a statistical work.

Together with his late co-writer, Richard Hernstein, Murray tackles what has to be the most controversial question ever asked by a scientist: that of the link between race and IQ.

I’ve only gotten through that *one* chapter and the plainness of prose there is haunting, to say the least:

The difference in test scores between African-Americans and European-Americans as measured in dozens of reputable studies has converged on approximately a one-standard-deviation difference for several decades. Translated into centiles, this means that the average white person tests higher than about 84 percent of the population of blacks and that the average black person tests higher than about 16 percent of the population of whites. The average black and white differ in IQ at every level of socioeconomic status (SES), but they differ more at high levels of SES than at low levels. […] The B/W difference is wider on items that appear to be culturally neutral than on items that appear to be culturally loaded.

[…] How do African-Americans compare with blacks in Africa on cognitive tests? This question often arises in the context of black-white comparisons in America, the thought being that the African black population has not been subjected to the historical legacy of American black slavery and discrimination and might therefore have higher scores. […] It has been more difficult to assemble data on the score of the average African black than one would expect. […] One reason for this reluctance to discuss averages is that blacks in Africa, including urbanized blacks with secondary educations, have obtained extremely low scores. […] In summary: African blacks are, on average, substantially below African-Americans in intelligence test scores.

[…] The question that remains is whether black and white test scores will continue to converge. […] If black fertility is loaded more heavily than white fertility toward low-IQ segments of the population, then at some point convergence may be expected to stop, and the gap could even begin to widen again. For now, the test score data leave open the possibility that convergence has already stalled. For most of the tests we mentioned, black scores stopped rising in the mid-1980s.

[…] The observed ethnic differences in IQ could be explained solely by the environment if the mean environment of whites is 1.58 standard deviations better than the mean environment of blacks. […] Environmental differences of this magnitude and pattern are implausible. Recall further that the B/W difference (in standardized units) is smallest at the lowest socioeconomic levels. Why, if the B/W difference is entirely environmental, should the advantage of the “white” environment compared to the “black” be greater among the better-off and better-educated?

[…] IQ is substantially heritable, somewhere between 40 and 80 percent. […] The broadest conception of intelligence is embodied in g. […] Whites and blacks differ more on the subtests most highly correlated with g, less on those least correlated with g. […] Once again, the more g-loaded the activity is, the larger the B/W difference is, on average. […] At the same time, g or other broad measures of intelligence typically have relatively high levels of heritability. This does not in itself demand a genetic explanation of the ethnic difference, but by asserting that “the better the test, the greater the ethnic difference,” Spearman’s hypothesis undercuts many of the environmental explanations of the difference

—Murray, The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life

I’m pretty sure I’ll get through the Wrong book. I’m not too sure about Murray’s. Nonetheless, they’ve both given new meaning to the idea of a “difficult” read.

With Do Not Disturb, I am being asked to confront the frightening possibility that Africa’s success story is actually a “totalitarian, police state.” And with The Bell Curve, I am being asked to consider the idea that of all the races in the world, mine might, after all, be the one nearest to the ape.

… Closest to nature.

I have to be honest: For #14, I had settled on “No Quarter” by Led Zeppelin—yet another psychedelic Ferris ride—until the almighty Spotify algo led me back to Jimi’s free-associative genius.

I’d taken a break from Jimi. I’d taken a break from cannabis. I needed it. But I’m back now. To Jimi Hendrix, not cannabis.

If Led Zeppelin is a Ferris ride, then Jimi Hendrix is a speedboat pulling you back-stroke across a horizon-less ocean. Your feet are tied to the back motor. The white foamy water cruises swiftly by your face as Jimi waxes trigger-happily on each riff.

In any case, I can’t think of a better track against which to test Senghor’s thesis.

If the founding father of Senegal is correct, then my instant stank-face each time Jimi mutilates his Stratocaster strings should be an expression of the very “sexual impression” evoked by the final 10 minutes of this 1995 Madilu show.

More importantly, the attendant subjective experience there should be fundamentally distinct from that of the “missing or unnatural rhythm” of such “European music and plainsong” as No Quarter. Or Stairway to Heaven. Or Frank Zappa’s Muffin Man. Or Trip Hazard’s Rat Race.

But—to Senghor I ask—is it?

That’s the project, folks. See you at #15!